Freed after years in extremists' captivity, Jihan faced an agonising ultimatum: abandon her three small children fathered by an "Islamic State of Iraq and Syria" (ISIS) fighter or risk being shunned by her community.

"Of course I could not bring them home. They're ISIS children," said Jihan Qassem matter-of-factly, sitting in a sparse concrete structure she now calls home.

"How could I, when my three siblings are still in ISIS hands?," she added, highlighting the harsh reality that the children serve as constant reminders of the brutalities inflicted on the closed, tight-knit Yazidi community by ISIS.

Dozens of Yazidi women and girls systematically raped, sold and married off to extremists after being abducted by ISIS from their ancestral Iraqi home of Sinjar in 2014 have faced the same gut-wrenching dilemma. What to do about the children born of these forced unions?

![Displaced Iraqi Yazidi children stand next to a tent at a camp in Khanke, in Iraq's Dohuk province, on June 24th, 2019. Dozens of Yazidi women and girls who were abducted by ISIS are facing a gutwrenching dilemma: either leave their kids fathered by ISIS behind or risk being shunned by their communities. [Safin Hamed/AFP]](/cnmi_di/images/2019/07/22/19028-yazidi-children-600_384.jpg)

Displaced Iraqi Yazidi children stand next to a tent at a camp in Khanke, in Iraq's Dohuk province, on June 24th, 2019. Dozens of Yazidi women and girls who were abducted by ISIS are facing a gutwrenching dilemma: either leave their kids fathered by ISIS behind or risk being shunned by their communities. [Safin Hamed/AFP]

Now freed, the women are desperate to heal from the wounds inflicted on the conservative minority -- but raising extremist offspring would make closure impossible, they said.

Kidnapped at 13, Jihan was forced to marry a Tunisian ISIS fighter at 15 and then fled with him and their children from ISIS's bombarded Syrian holdout of al-Baghouz four months ago.

When US-backed forces learned she was Yazidi, they whisked her and her two-year-old boy, year-old girl and four-month-old infant to a north-east Syria shelter hosting other mothers from the brutalised minority.

The safe-house, known as the Yazidi House, circulated her photograph on Facebook and her older brother Saman, still in northern Iraq, recognised his long-lost sister.

He wanted her home. But without the children.

After days of an anguished back-and-forth, Jihan decided she would leave her infants with Syrian Kurdish authorities in exchange for what she said was her real family.

"They were so young. They were attached to me and I to them... but they're ISIS children," she murmured.

She said she does not have any pictures of her children and doe not want to remember them.

"The first day is hard, and then little by little, we forget them," she said.

'No one asks about them'

For centuries, Yazidis who married outside the sect -- even against their will -- were ex-communicated.

Girls forcefully taken by ISIS in 2014 risked suffering the same fate, but a landmark decree by Yazidi spiritual leader Baba Sheikh said survivors of ISIS's sexual abuse should be honoured by the community.

That compassion however has not been extended to their children.

In April, the Yazidis' Higher Spiritual Council issued an ambiguous decree welcoming "children of survivors," sparking hope of a second reformation to accept those born of a Yazidi mother and ISIS father.

But a ferocious backlash from conservative Yazidis prompted the Council to clarify that nothing had changed: it would only welcome children born to two Yazidi parents.

Any further reform was seen as a threat, opening the floodgates of change to a traumatised community, said Yazidi activist Talal Murad.

"If there is this kind of change in the creed, other things could change too -- there will be a breakdown, a total collapse of the Yazidi religion," said Murad, who also heads Ezidi24, an outlet covering Yazidi affairs.

Council representative Ali Kheder told AFP the debate was not solely about dogmatic reform.

"First, according to Iraqi law, any child with a missing father will be registered as a Muslim, automatically," said Kheder in the Council's headquarters in Sheikhan.

Islamic law, on which the Iraqi constitution is based, stipulates that religion is inherited from the father.

Psychologically too, Kheder said the Yazidi society remained too scarred by the prolonged abduction of their own people to accept raising the children of their abusers.

"Until now, we have thousands of Yazidi women and girls in ISIS hands. No one asks about them. They ask about a few children that can be counted on one hand," said Kheder.

The Council said it does not keep statistics on returning Yazidi survivors with infants born of rape.

Flesh, blood, tears

While most Yazidi mothers leave their children at the Yazidi House in Syria, some brought ISIS-born infants home to Iraq. They declined interviews because of the subject's sensitivity.

One woman insisted to her Yazidi family that she would raise her year-old infant fathered by a missing ISIS fighter, but balked when she discovered she could not acquire Iraqi identification papers for him as his father was not present.

She gave him up for adoption, her doctor said.

Another 18-year-old arrived in Iraq in the spring after finally being freed, but was heavily pregnant by her ISIS captor, according to a social worker involved in her case.

She spent weeks in a safe-house without her family's knowledge until she gave birth, sent the newborn away and joined her relatives in a displacement camp.

Last year, five children born to Yazidi mothers and ISIS fathers were left at an orphanage in Mosul, which helped local Muslim families adopt them, according to Mosul's director of women and children's issues Sukaynah Younes.

They are now registered as Muslim.

The psychological impact of this separation will likely be long-lasting. Jihan herself still seemed torn.

Weeks ago, she had described her children to a social worker as her "flesh and blood," saying she missed them.

While she sounded more detached when speaking to AFP, a shy smile crossed her face as she remembered them. When she was out of her brother's earshot, she cried quietly.

"If it was up to me, I would have brought them," she said.

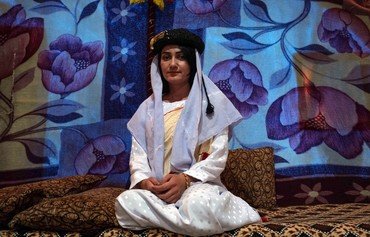

![Iraq's Yazidi Jihan Qassem, 18, at a makeshift house in an area housing many displaced people on the outskirts of the north-western Iraqi town of Baadre on June 25th, 2019. Jihan had to abandon her three children fathered by her ISIS husband, or be shunned by her community. [Safin Hamed/AFP]](/cnmi_di/images/2019/07/22/19027-yazidi-jihan-600_384.jpg)

The Suffering of Freed Yazidi Women: Jihan Qassim, a Yazidi woman from Iraq, at a temporary house in an area where many displaced people live on the outskirts of Baadra, northwest of Iraq, in a picture taken on 25 June 2019. Fear of becoming isolated in her community has forced Jihan to abandon her three children because their father is an "Islamic State of Iraq and Syria" (ISIS) element. Safin Hamed/AFP. A few days ago, in Raido (???), and I think that she is talking about the same person, but she didn’t mention her name. She was cited as saying that she was 13 in 2014 when she was kidnapped and married off although she was a minor. She now has three children (aged 2 years, 1 year and several months and four months (a baby)). “I left them at al-Hawl [Camp], and the 2-year old was calling on the mother, saying, ‘Mom, take me with you.’ This was repeated several times. The second child can’t talk yet. She said she cleaned the baby, changed its [Illegible], and bought it a [Illegible]. She gave it her two breasts for the last time. She said they’re young and will forget me. This is a tough situation, as love and hatred are combined in children. Aren’t there any people in the world who can help those women by providing a decent living for them with their children in any means possible? I fear lest the innocent children fall in the hands of criminals and child traffickers. We’re all victims of rulers, traders of blood and tragedy. M. Irbil, Iraq

Reply2 Comment(s)

This is a right word and a wrong implication! Where’s your website from the crimes of the "Islamic State of Iraq and Syria" (ISIS) against Yazidis before you mention such cases?

Reply2 Comment(s)